Innovators: How Collaboration Builds the Future

Why I Read It

I picked up The Innovators because I wanted to understand how technology really came to be — not as a single flash of genius, but as a relay race carried across generations.

Walter Isaacson traces that journey from Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage to Vannevar Bush, Doug Engelbart, Alan Kay, and Steve Jobs — showing how the digital world grew through collaboration, iteration, and imagination.

For me, it wasn’t just a history book; it felt like a guide on how to think, build, and work with others. I wanted to see how each generation stretched the limits of what was possible — and what lessons I could bring into my own work, blending creativity, technology, and long-term vision.

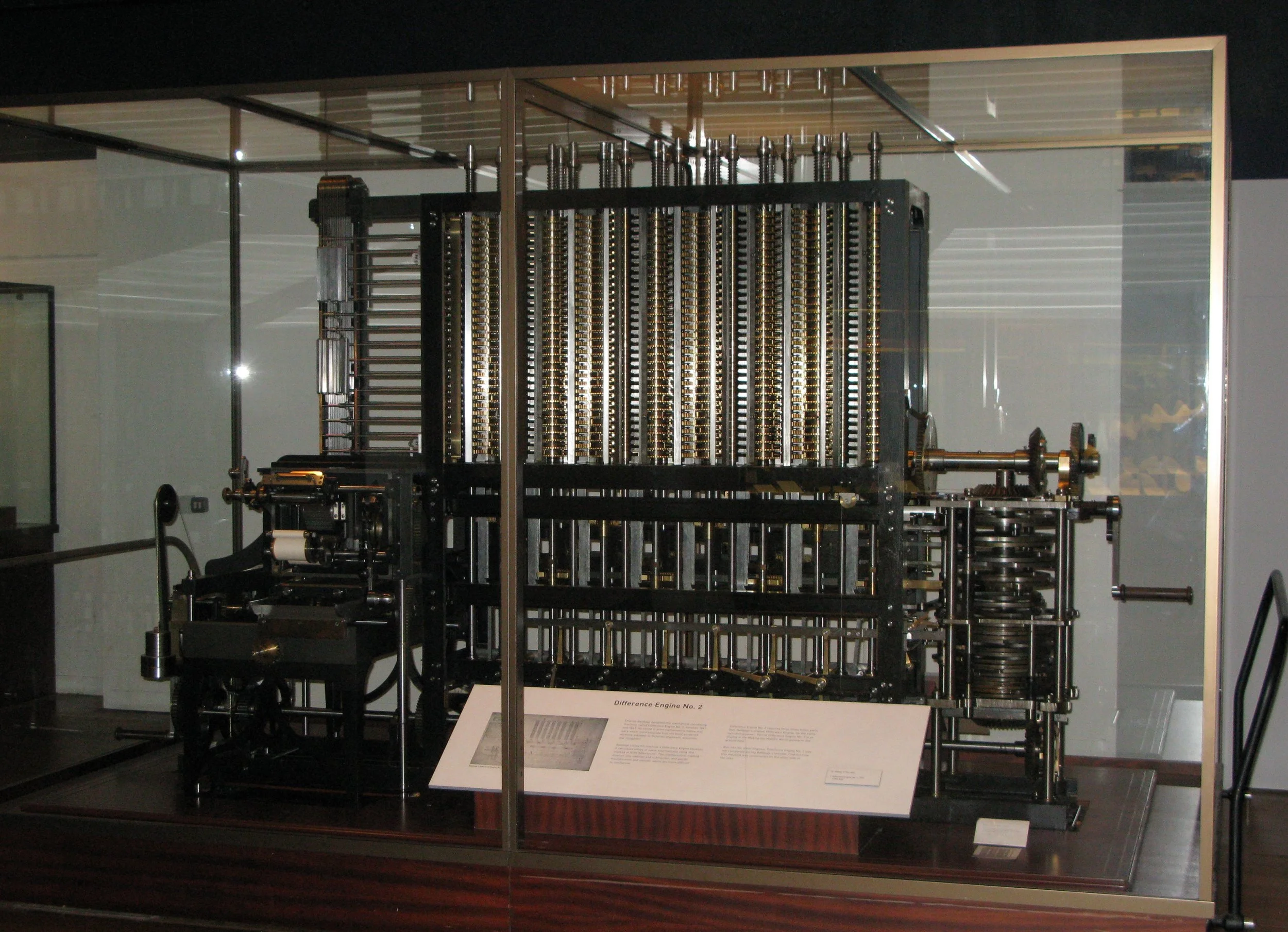

Babbage Difference Engine at the London Science Museum

“The best innovators were those who understood the trajectory of technological change and took the baton from those who preceded them.”

What I Learned

AI-generated

🧠 The Foundations of the Digital Mind (1840s–1960s) — Imagination, Logic & Connection

Ada Lovelace saw beyond Charles Babbage’s mechanical engine and imagined a machine that could compose music or art if given the right instructions.

She called it “poetical science”—where logic meets creativity. Her insight set the philosophical tone for everything that followed.

Nearly a century later, Alan Turing asked a radical question: “Can machines think?”

His theoretical “Turing Machine” became the blueprint for computation itself, while his wartime code-breaking proved that machines could augment human intelligence—not replace it.

Then came Vannevar Bush and J.C.R. Licklider, who envisioned computers as tools for collaboration and connection.

Bush’s idea of the Memex anticipated hyperlinked knowledge, and Licklider’s “man–computer symbiosis” paved the way for ARPANET — the Internet’s prototype.

AI-generated

⚙️ The Hardware Revolution (1947–1960s) — From Switches to Systems

At Bell Labs, William Shockley, John Bardeen, and Walter Brattain built the transistor — a tiny silicon switch that replaced bulky vacuum tubes.

That single invention shrank machines from room-sized giants to pocket-sized tools and laid the foundation for the entire digital age.

A decade later, Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce etched entire circuits onto a single chip, birthing the microchip and the companies that defined Silicon Valley.

Their work unlocked Moore’s Law—the principle that computing power would double roughly every two years, setting off an era of exponential progress.

Digital illustration of a silicon microchip.

Then came Doug Engelbart, whose 1968 “Mother of All Demos” introduced the world to the mouse, hypertext, and video conferencing—decades ahead of their time.

His belief was simple yet profound: technology should amplify human capability, not replace it.

Early personal computer with a graphical user interface (GUI).

AI-generated

💡 The Personal Computing Revolution (1970s–1990s) — From Interface to Culture

At Xerox PARC, Alan Kay envisioned the “Dynabook” — a portable computer for creativity and learning.

The lab’s open, experimental culture birthed the graphical user interface (GUI), icons, and windows — the blueprint for how humans would one day interact with machines.

Bill Gates then scaled that vision, shifting the focus from hardware to software.

By licensing DOS and standardising personal computing, Microsoft made digital tools accessible to millions — turning computers from luxury machines into everyday essentials.

Finally, Steve Jobs fused art and engineering.

He took the ideas born at PARC and turned them into experiences — simple, elegant, and emotional.

For Jobs, simplicity wasn’t just aesthetic — it was moral clarity: technology should empower, not overwhelm

Apple’s iPhone

AI-generated

🔍 Google, Facebook & OpenAI (2000s–2020s) — From Search to Social to Sentience

Larry Page and Sergey Brin’s PageRank algorithm turned the web’s chaos into order.

Their genius wasn’t data alone—it was the feedback loop that they learnt from every search.

Mark Zuckerberg then built on that connected infrastructure, transforming the web from an information network into a social network — one that mapped human relationships as precisely as Google mapped knowledge.

And now, Sam Altman and OpenAI represent the next inflection point — tools that don’t just organise information or people but collaborate with us.

It’s the dawn of the agentic age — where software doesn’t just answer, it assists, reasons, and builds alongside humans.

Artifical Intelligence

How Innovation Applies to Life and Work

Collaborate across generations. Learn from those before you; build for those after you.

Be a product person. Care about design, usability, and clarity — whether you’re coding, writing, or managing.

Create feedback loops. Build systems that learn and improve from interaction.

Take audacious risks. The impossible only becomes possible through persistence.

Balance open and proprietary. Progress thrives when ideas are shared but sustained by viable models.

Value proximity and community. Innovation isn’t remote; it’s relational.

Shift from consumption to creation. Meaning comes from contributing, not just observing.

Personal Reflection

Reading Innovators reframed how I see creativity. It's not about being the first; it's about bridging the gaps left by others and looking to the past to shape the future.

It reminded me why I'm drawn to learning across disciplines and why I enjoy building small systems like AION to test ideas in practice.

I realised that innovation is a mindset that involves blending disciplines, collaborating with others, and continuously iterating.