Apprentice Scholar: What Nicomachean Ethics Taught Me About Building a Life Worth Funding

Who Am I?

I didn’t come to Aristotle as a student chasing grades.

I came to him in my mid-20s, after resigning from a stable job, turning down a promotion and pay rise, and stepping deliberately into what I’ve started calling my apprentice scholar phase.

I’m trying to work out how to build a life that is:

financially solid,

intellectually serious, and

ultimately useful to other people.

So I picked up Nicomachean Ethics not as an academic text, but as a manual.

What I found was uncomfortably direct: Aristotle isn’t really talking about abstract “virtue”. He’s talking about the kind of person you are becoming when nobody’s watching – and whether that person, if given resources and power, would actually be good for anyone.

This post is my attempt to map his ideas onto my own life and the person I want to be at 40.

Who I Want to Be at 40

When Aristotle talks about the “highest human good” – activity of the soul in accordance with virtue – I immediately picture a specific version of myself at 40:

A philanthropist, backing people who are where I am now.

A builder–entrepreneur, who has gone through a long apprentice phase of serious learning.

A writer and thinker, with at least one book out, documenting a polymath, “philosopher-king” style life.

Someone who uses knowledge and capital to create systems and opportunities for others.

For me, that’s what eudaimonia looks like:

Not chilling on a beach, but living as a wise, generous systems-builder who lifts others up.

Happiness isn’t the absence of effort. It’s having the right kind of effort – directed at the right things.

Aristotle makes it brutally clear: you don’t become that person by accident. You get there by shaping your character through repeated actions, until good choices are almost instinctive.

That’s the project I’m in the middle of.

Plato’s Inner Republic vs Aristotle’s Virtuous Activity

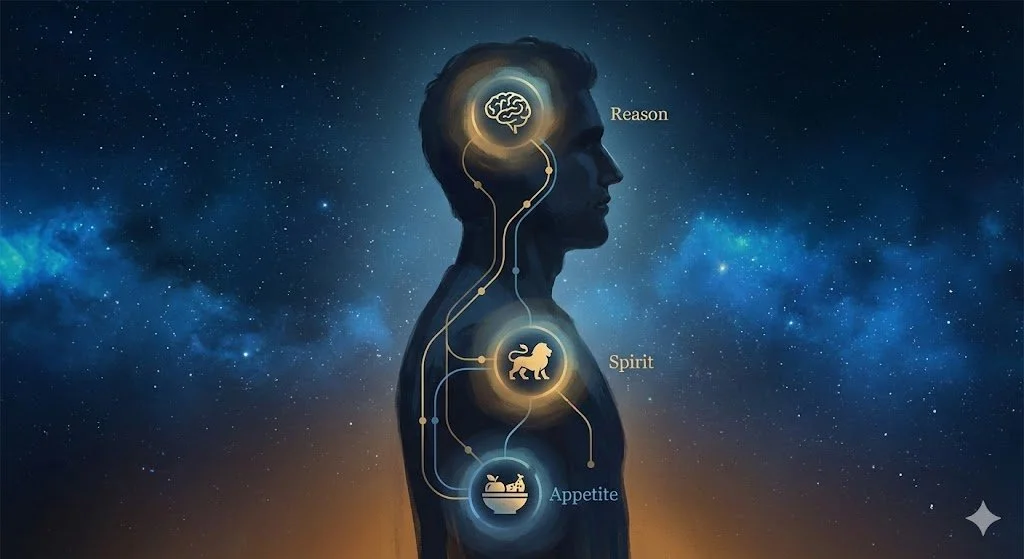

Reading Aristotle straight after Plato, I started to see the join between them.

Plato talks about justice as inner harmony – reason, spirit, and appetite all doing their proper work.

Aristotle talks about living “in accordance with virtue” – choosing the right action, in the right way, at the right time.

In my head, those ideas fuse into a single picture:

A just or virtuous person is someone whose inner life is ordered enough that they naturally lean towards good actions and reliably avoid vicious ones.

Cruelty, indulgence, cowardice, spite – these aren’t just individual mistakes; they’re signs of a badly governed inner city.

I wrote in my notes that I’m trying to build my inner republic now so that whatever systems I design later – in finance, space, risk, or philanthropy – aren’t just clever but actually good.

If the person at the centre is disordered, no amount of “impact” language will fix it.

The Loner Trap: Balance, Not Self-Erasure

One of Aristotle’s most famous ideas is the “mean” – the virtuous point between two extremes.

When I applied that to my own life, a warning light came on.

If I went full monk – just coding, reading, studying, no social life, no sport – it would look virtuous from the outside. But internally it would push me towards bitterness, isolation, and probably weirdness.

I don’t want to be a brain in a chair.

I want a life that includes:

deep work and study,

friendship and community,

physical challenge,

and space for simple enjoyment.

So the “mean” I’m aiming for is:

Enough solitude to think and build, but enough life to stay human.

Monk Mode is a phase, not an identity. Aristotle helped me see that going too far into isolation would actually make me less virtuous, not more.

A Quick Virtue Audit: Courage, Liberty, Magnificence, Temperance

Reading the chapters on specific virtues forced me into a bit of a self-audit.

Courage

On courage, I’m actually proud of myself.

I resigned from a stable job. I turned down a counter-offer with more money and promotion. I chose the uncertain “philosopher path” over corporate comfort.

That doesn’t make me a hero, but it does prove I’m not paralysed by fear.

Liberty

Liberty, for me, is the freedom to shape my days, my learning, and my projects.

I’ve always learnt the most when I step outside formal systems – university, corporate structures, prescribed career ladders. Leaving was my way of saying, 'I want to own the script.’

Magnificence

'Magnificence' is Aristotle’s word for spending and acting on a big scale for good purposes.

I’m not there yet, but the intent is real:

I want to think as big as possible about humanity’s future – space, finance, infrastructure, and education.

I’m okay with failure if something useful comes out of the attempt.

I’d rather overshoot with good intentions than stay small and safe.

This is the virtue that scares me most, because it implies a level of responsibility I don’t yet have the competence for. But it’s also the one that keeps me moving.

Temperance

Temperance is my active work-in-progress.

I already live by some non-negotiables, but temperance also covers sleep, food, distractions, and time. This is where I feel the gap most.

I often sleep 8–9 hours when I know I could function on 6–7. I lose blocks of time to disorganisation rather than doom-scrolling. It’s not dramatic, but it’s still a form of self-indulgence.

If courage and liberty got me out of the old life, temperance is what will keep the new one sustainable.

Money, Need, and Why I’m Not “Just the Space Guy”

Aristotle spends time on justice in exchange and the role of money. It sounds abstract, but it sharpened something for me.

Money is a representation of need and exchange, not an end in itself. That’s obvious on paper but easy to forget in the real world.

But what really excites me sits one level up:

Moving whole industries from fragile spreadsheets to real-time, automated, blockchain-backed systems.

Asking why we only see Jarvis-style co-pilots, planetary councils, and space economies in sci-fi – and what it would take to build their boring, regulatory, and actuarial foundations in real life.

A law, history, and philosophy lens should guide the design of those systems, ensuring they not only function technically but also make ethical sense.

Aristotle’s discussion of fairness, justice, and proportionality in exchange feeds straight into that mission. I don’t just want clever pricing models; I want systems that treat people and capital fairly over decades.

So yes, I’m starting with space insurance and risk. But the real game is institutional architecture.

My Intellectual Stack: Technē, Epistēmē, Phronēsis

One of my favourite parts of Nicomachean Ethics is Aristotle’s breakdown of the intellectual virtues:

Technē – craft or making.

Epistēmē – scientific knowledge, theory.

Phronēsis – practical wisdom, good judgement about action.

It gave me a clean way to think about what I’m building in myself.

Technē is all the system-building:

Coding in Cursor.

Designing the AION risk engine and dashboards.

Learning how to turn ideas into working software.

Epistēmē is my School of Thought plan:

Maths, physics, philosophy, history, astronomy, Arabic.

Reading people like Plato, Aristotle, Franklin and Jefferson and trying to understand how they thought, not just what they thought.

Phronēsis is the missing piece I’m trying to construct from scratch:

No boss or mentor can hand this to me.

It has to be built from repeated decisions, feedback, and honest reflection.

My deepest fear isn’t “ending up broke”. It’s speaking confidently about things I haven’t truly earned the right to speak on.

I don’t think of myself as “naturally clever”. I think of myself as someone trying to manufacture intelligence through disciplined reading, building, and error.

Akrasia, Sleep, and the Battles I’m Actually Fighting

Akrasia – knowing the good and failing to do it – is one of Aristotle’s big themes.

In my life right now, the main battleground is boring and specific: sleep and structure.

I want to get up earlier.

I know that an extra hour or two each morning, consistently, would compound into something serious.

But in practice, I still drift towards 8–9 hours instead of 6–7.

The good news is that I’ve already won some important battles:

Daily reading.

I read at least 30 minutes every day now. That single habit has transformed how I see the world more than any course.No mindless social media.

No TikTok, no Instagram. I only use X as an information firehose, not as a slot machine.Using AI as a lever, not a distraction.

I treat AI tools as time compression – help with coding, research, and planning – not as toys.

So the work now is less about “overcoming addiction” and more about tightening the screws on time and energy. The goal is simple: live closer to what I already know.

Friendship, Self-Love, and Being at War With My Own Memory

Aristotle’s sections on friendship were uncomfortably accurate.

He talks about three main types:

Friendships of pleasure – people you enjoy spending time with.

Friendships of utility – people who are useful to you in some way.

Friendships of virtue – people who share a commitment to the good, where you help each other become better.

Looking at my own life:

Most of my friendships right now are pleasure friendships – sport, jokes, shared history. I value them.

A smaller group are virtue-leaning – people I can actually talk to about ideas, ethics, and long-term plans. These are becoming more important to me.

Purely utility relationships don’t appeal. I’m not interested in using people as tools.

On self-love, I had to admit something harder:

I often feel like I’m at war with myself.

I have a very vivid memory of my whole life. Random negative moments from childhood up to last week will resurface without warning. It’s like my brain is optimised to highlight failures and embarrassments, not progress.

Aristotle makes a helpful distinction:

Bad self-love: chasing pleasures that harm your deeper self.

Good self-love: pursuing what truly benefits your rational, long-term self.

What I’m trying to do now is train my memory and attention to act more like a good friend than a bully. To notice growth and effort, not just mistakes.

Philosophy isn’t a magic cure, but it gives me a vocabulary and a framework for this inner work.

My Three Personal Laws

If I treated my life as a small city-state and had to write a mini-constitution, based on Aristotle, it would currently have three core laws:

Temperance.

Lifelong learning.

Love and respect.

They’re simple on paper. They’re harder in practice. But they give me a direction.

Plato gave me the image of an inner republic – a soul ordered like a just city.

Aristotle is giving me the operations manual for how to actually run it.

I’m still early in the process. I’m in my mid-20s, not my 40s. A lot can go wrong between here and there.

But if I can keep aligning my habits, friendships, work, and systems with the virtues Aristotle describes, then the philanthropist-builder version of me at 40 feels less like a fantasy and more like a realistic endpoint of a long series of choices.

For now, that’s enough.