Cicero and the Seventy-Year Harvest: Higher Law and Long Games

I didn't know much about Cicero before reading his Selected Works. I knew he was a Roman statesman, that he'd been killed for opposing Mark Antony, and that some of his letters survived. That was about it.

After working through On Duties, On Old Age, and his correspondence, something shifted. What emerged wasn't just a politician or a philosopher, but a lawyer-philosopher-orator-statesman hybrid—exactly the kind of polymath I'm trying to become, just in another century and a collapsing republic.

He left me with two ideas I needed to hear at 27.

First: the clash between doing what's right and doing what's advantageous is an illusion. In reality, they are inseparable.

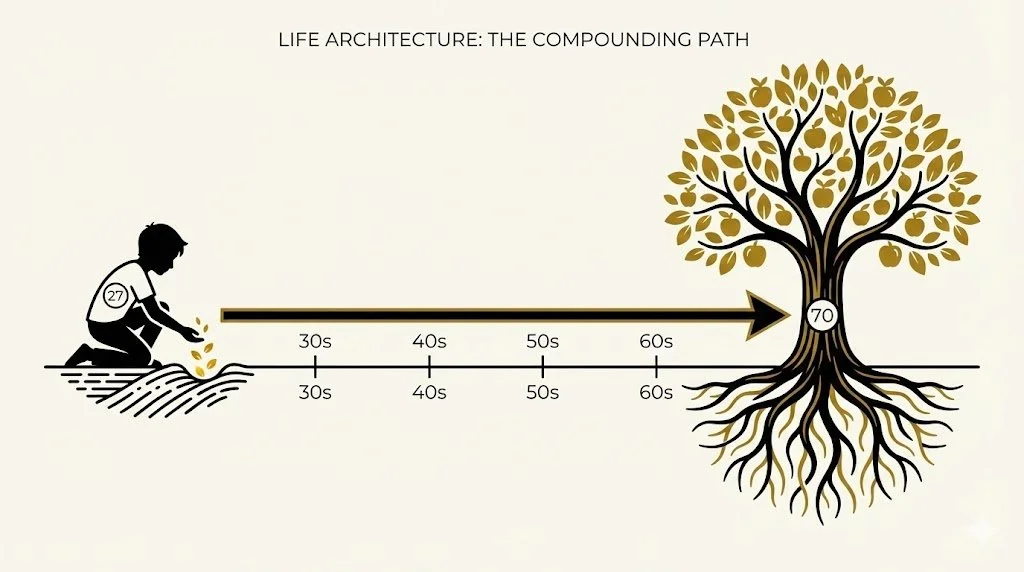

Second: a life is judged at seventy, not twenty-seven. The qualities that matter—thought, character, judgement—don't peak early. They compound over decades.

Sitting in London, halfway through building AION and choosing a harder path over comfort, I needed both of those truths.

The Hybrid I'm Building Toward

Cicero was the ideal hybrid in a previous life.

Lawyer — trained in rhetoric and Roman law, defending clients in courts where even the worst criminals could walk free if they had money.

Philosopher — obsessed with Greek ethics, translating Stoic and Platonic ideas into Latin so Romans could actually use them.

Orator — one of history's most persuasive public speakers, shaping policy through words alone.

Statesman — consul, senator, defender of the Republic until the end.

He didn't live these as separate careers. He did them all at once. He was building systems of thought while defending the constitution; writing philosophy while standing in the Forum arguing cases.

That's the model I see for myself—not picking one lane, but operating across multiple domains:

Law and governance (understanding how institutions actually work)

Philosophy and systems thinking (first principles, ethics, long-term frameworks)

Public influence (writing, speaking, shaping how people think)

Building (AION, the space economy, tools that actually matter)

People used to ask me: "Why do you study history? Why do you care about the past?"

I did a history degree first, then converted to law. On paper, it looked scattered, unfocused. Why not just do law from the start?

But studying history wasn't a detour. It was the foundation.

History shows you how humans think, how societies collapse, how institutions evolve—or fail to evolve. It shows you patterns that repeat across millennia. Rome and London aren't that different: power structures, corruption, the gap between law and justice. It's all there, just wearing different clothes.

The past shapes the future. And if you don't understand where institutions came from, you can't build better ones.

That's why I read Plato, Aristotle, Cicero. Not for nostalgia. Not for decoration. But because these thinkers built the operating systems we're still running on—and most people don't even know it.

Cicero also showed me something critical: you don't start as the hybrid. You build towards it.

He spent decades as a lawyer and orator before writing philosophy. He earned credibility through cases, speeches, and defending the Republic. Only then did his words on ethics and duty carry real weight.

That's where I am now: the apprentice phase. Starting at the bottom.

Building AION not because it's the final form, but because it's the foundation that earns me the right to speak later.

You don't become a Cicero by starting with philosophy. You get there by building proof-of-work first—and only then translating what you've learnt into frameworks other people can use.

Higher Law vs State Law: Naming What I Already Felt

The part of Cicero that hit hardest was his concept of Natural Law—the idea that there's a higher standard above any state, any senate, any company.

He describes true law as right reason in accordance with nature: a law that commands us to do our duty and forbids us to do wrong, valid everywhere and for all time. There isn't one law for Rome and another for Athens, or one for now and another for later—there is a single, unchanging standard that all nations and all people ultimately fall under.

I've felt this my entire life but never had the language for it.

UK law, US law, corporate policies—they're all local and temporary. They can be bent, captured, or corrupted. But there's a deeper sense of right and wrong that exists regardless of what any institution says.

When I left KPMG, most people thought I was choosing moral righteousness over practical advantage:

Stable salary vs risky bet on the space economy

Promotion path vs unknown outcome

Security vs "principle"

Cicero reframes that completely.

He argues—and I believe this now—that the clash between right and advantage is the illusion. In reality, they are inseparable. Choosing the morally right path IS advantageous in the long run. Any conflict is just a failure of vision.

Staying at KPMG wasn't advantageous. It was slow death: monthly paycheques in exchange for sleepwalking. Reports no one read. Work that didn't compound. No growth in the things that actually matter.

Leaving wasn't a noble sacrifice. It was seeing through the illusion that staying was ever an advantage at all.

That's Stoic wisdom disguised as career advice. And it's the hardest thing to explain to people still inside the system.

When Right and Advantage Look Like Enemies

Cicero's teacher, Panaetius, framed almost every moral decision with three questions:

Is this morally right or wrong?

Is this advantageous or disadvantageous?

If they seem to clash, what do I do?

The Stoic answer—Cicero's answer—is that question three is a trap. If something is truly right, it will be truly advantageous.

Most people live inside that illusion.

They think:

"I could be honest with my client, but then I'd lose the deal."

"I could speak up about this problem, but it would hurt my career."

"I could leave this job, but I need the security."

In each case, they're treating right and advantage as opposing forces—and consistently choosing "advantage".

Cicero argues the opposite. If you could see the full picture—if you thought in decades instead of quarters—you'd realise the dishonest deal poisons the relationship, the silence compounds the problem, and the "secure" job is slowly killing you.

Right and advantage only clash in the short term, and only when your thinking is narrow.

I've tested this in my own life.

I've been on the receiving end of people choosing selfish advantage over what was fair or moral. Friends who cut corners. Colleagues who lied to protect themselves. People who optimised for their own gain at someone else's expense.

Every time, I watched them win in the short term—and lose in the long term.

The shortcuts compound into reputational damage. The lies harden into patterns. The selfish choices isolate them.

Meanwhile, the times I chose what felt "right" over what felt "smart"—when I refused to cheat, refused to lie, refused to take advantage—those decisions did not feel advantageous in the moment.

But they were.

Because integrity compounds. Trust compounds. Self-respect compounds.

At 27, I'd rather be poor and honest than rich and ashamed of how I got there.

Cicero's point isn't that virtue always wins immediately. It's that virtue is the only thing that wins on a long enough timeline.

And this only really makes sense if you're thinking in decades, not quarters.

Pretend vs Do: The Education Scam

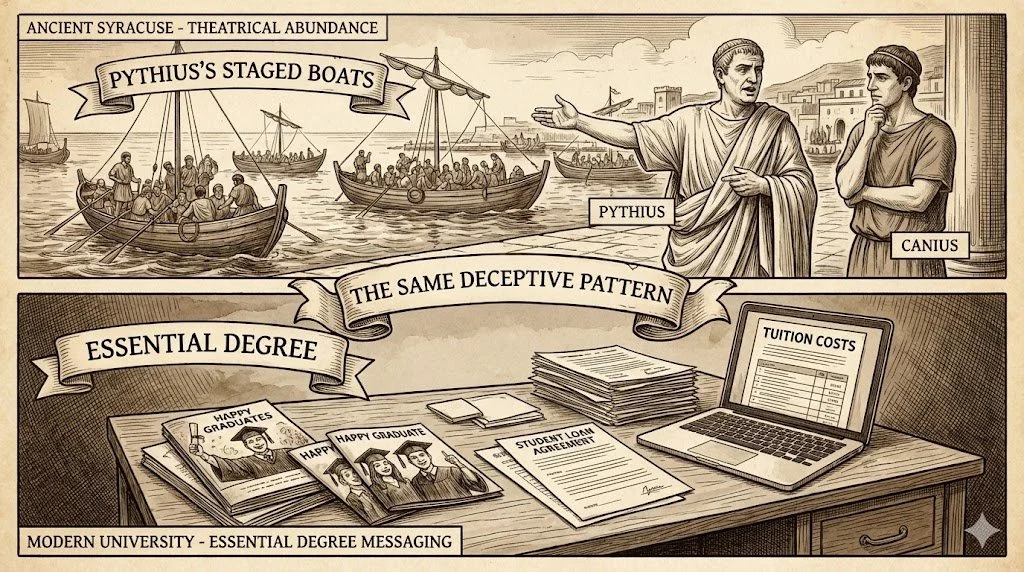

There's a story in Cicero's On Duties that felt like a blueprint for every scam in history.

A Roman gentleman named Canius wanted to buy a small estate by the sea. A banker called Pythius owned the perfect property—but business was slow, the harbour was dead, and the place wasn't worth what Pythius wanted for it.

So Pythius staged a scene.

He invited Canius to dinner at the estate. Then he hired every fisherman in Syracuse to do their day's fishing directly in front of the property. Boats everywhere. Nets thrown, fish hauled in and piled up at Pythius's feet.

Canius watched and thought: All the fishing activity in Syracuse happens right here.

He bought the property on the spot. Paid full price. Bought the furnishings too.

The next day, he invited friends over. He arrived early, ready to show them the booming harbour.

No boats. No fishermen. Nothing.

He'd been scammed. The whole thing was theatre. Pythius had created fake demand, staged prosperity, and walked away with the money.

When Canius asked a neighbour if there was some fisherman's holiday, the reply was simple: "Nobody does fish here; yesterday I couldn't think what had happened."

When Canius tried to sue, the lawyer Aquilius gave a definition that became classic in Roman law:

Fraud is pretending one thing and doing another.

That line is 2,000 years old, and I see it everywhere in 2025.

But not where most people look.

The biggest "pretend vs do" scam I've lived through isn't ESG or greenwashing.

It's the education system.

Pretend: "You need a university degree to succeed. It's essential. Without it, you're nobody."

Do: Accumulate £50,000 in debt, spend three years studying things you'll never use, graduate with no practical skills, and then compete for jobs against people who've been building while you were in lectures.

Pretend: "Corporate careers mean stability, growth, respect."

Do: Sleepwalk through reports no one reads, learn nothing that compounds, trade time for paycheques, and wake up at 27 realising you've wasted some of your sharpest years.

Pretend: "Young people need more education."

Do: They need focus, encouragement, and permission to start building earlier—not more debt and distraction.

I lived this.

I spent years on a law degree I never truly wanted because that's what you're "supposed" to do. Then years at KPMG doing work that had no real compounding value.

All the while, society was pretending this was the path to success, while actually creating a generation:

drowning in debt,

starting their real education in their late twenties,

and competing while already behind.

If I'd been encouraged to start building at 18 instead of 21, I could have been helping humanity years earlier.

But the system doesn't want that.

The system wants tuition fees. It wants compliance. It wants workers trained to follow processes, not builders trained to question whether the process makes sense.

Cicero's definition of fraud—pretending one thing and doing another—fits perfectly.

The education-industrial complex pretends degrees are essential while doing the opposite: creating debt, delaying practical experience, and teaching people to optimise for credentials instead of competence.

This is why I'm drawn to building transparent systems.

Not because technology magically fixes corruption, but because architecture can make pretending harder.

If young people could see, in one place:

the actual ROI of degrees vs practical experience,

the real career paths of successful builders (many without traditional credentials),

the cost-benefit of three years studying vs three years building,

...they'd make very different choices.

Pythius hired fishermen for a day to fake demand. Universities hire marketing teams to fake necessity.

The solution isn't better marketing. It's glass-box infrastructure—systems where the gap between what's promised and what's delivered is visible, traceable, undeniable.

That's what I'm trying to bake into my work. Not perfection. Not moral purity. Just honesty as infrastructure—a world where it's finally harder to pretend than to tell the truth.

The 70-Year Harvest: How Cicero Calms My Panic

At 27, I constantly feel behind.

Most of my peers have careers, mortgages, stability. They've been climbing corporate ladders whilst I've been starting over.

I'm in the same apprentice phase I described earlier—but now I'm looking at it through a seventy-year lens. Building AION from scratch, hoping I'm not too late to land at Relm when the employment cycle restarts, trying to prove I belong in an industry where everyone else has engineering degrees and I'm teaching myself through AI-assisted development.

It's hard not to panic about timelines.

Then I read Cicero's On Old Age, and something shifted:

"Great deeds are not done by strength or speed or physique: they are the products of thought, character, and judgement. And far from diminishing, such qualities actually increase with age."

Read that again.

The things that matter—thought, character, judgement—don't peak at 25. They don't even peak at 35. They compound over decades.

Cicero reframes the entire game. It's not about winning at 27. It's about laying foundations that your seventy-year-old self can be proud of.

Here's what I imagine at 70:

A successful business—self-sustaining, meaningful, something that actually matters

Real impact on humanity—not just wealth, but systems and ideas that help people

A charity or institution that helps others in the position I'm in now

A family where each person has their own path and purpose

A body still healthy and active—still playing sport, still moving

Still working in some form—not retired, but engaged, building, contributing

That life doesn't get built in your twenties. It gets built over five decades of compounding decisions.

Cicero describes old age not as decline but as harvest. The person who lives well reaps the results of decades of good character, good habits, good choices.

But he's clear: authority in old age isn't automatic. It's the "final result of well-spent earlier years." The harvest only comes if the foundations were laid in youth.

That's why I've adopted Cicero's daily practice.

Every night, I journal: what I built, what I thought, where I failed, what I learnt. It's a Pythagorean habit that Cicero borrowed:

"To keep my memory in training I adopt the practice of the Pythagoreans and, every evening, run over in my mind all that I have said and heard and done during the day. That is my intellectual exercise, my running-track for the brain."

This isn't productivity theatre. It's systems design for character.

Each day, I'm logging data points: small improvements, tiny failures, incremental learning. Over years, those compound into something that looks like wisdom. Over decades, they become the foundation of a life worth looking back on.

At 27, I'm not harvesting. I'm planting.

And Cicero's reminder is simple: the qualities that matter are still growing. I'm not behind. I'm early.

The panic dissolves when I shift the question from "Am I winning this quarter?" to "What will my seventy-year-old self think of the choices I'm making now?"

That's the only timeline that matters.

The Loneliness of High Standards

Here's the part no one talks about.

Cicero lived in a collapsing republic. The courts were bought. The richest criminals walked free. Power was rigged. Caesar, Pompey, Crassus—everyone was choosing personal advantage over principle.

And Cicero kept defending the Republic anyway.

He could have joined a triumvirate. He could have taken bribes. He could have stayed quiet and survived. Instead, he spoke out against corruption, against tyranny, against the erosion of law.

It cost him everything. Mark Antony had him killed. His head and hands were nailed to the Forum as a warning.

But his letters survived. His philosophy survived. His defence of higher law survived.

Reading him 2,000 years later, I realise: he gives you permission to be lonely.

Because the path gets lonely.

When you care about philosophy in a world that cares about football, you're isolated.

When you choose purpose over comfort, most of your peers won't understand.

When you live by higher law whilst everyone else optimises for personal advantage, you lose people.

I've experienced this. I've been on the receiving end of people choosing selfish advantage over what was fair or moral. Friends who cut corners. Colleagues who lied to protect themselves. People who optimised for their own gain at someone else's expense.

Right now, at 27, I don't have the circle I want. I don't have a group operating at the same standard. I'm building in silence, hoping the table I'm constructing will eventually attract people worth sitting at it.

Most people around me would rather watch football than talk about Cicero, Plato, or systems thinking—and that's fine. It's just not my path.

The loneliness isn't a flaw in me. It's the natural consequence of caring about things most people don't.

Cicero proves: loneliness isn't a bug. It's the cost of refusing to lower your standard.

So the question isn't: "How do I avoid loneliness?" It's: "Will I eventually find people operating at this standard too?"

I think the answer is yes—but only after the foundations are built. Only after proof-of-work. Only once the harvest starts to show.

You don't attract serious people by talking about seriousness. You attract them by being serious—by building, by doing the work, by living according to higher law even when no one's watching.

Cicero wrote:

"He was never less idle than when he had nothing to do, and never less lonely than when he was by himself."

That's the standard I'm aiming for.

Not "I tolerate being alone," but "I'm never less lonely than when I'm by myself"—because the work is meaningful, the ideas are alive, and I'm building something that matters.

At 27, that means accepting a simple equation: higher standards = fewer peers.

But the alternative—lowering my standards to fit in, choosing comfort over purpose, optimising for approval instead of integrity—isn't an option.

I'd rather be lonely and honest than surrounded by people I don't respect.

Cicero proves you can be isolated, rejected, even killed—and still win on a long enough timeline.

That's the bet I'm making.

Pleasure, Temperance, and the Life I'm Actually Building

Cicero is harsh on pleasure.

In On Duties, he quotes the philosopher Archytas:

"The most fatal curse given by nature to mankind is sensual greed. This incites men to gratify their lusts heedlessly and uncontrollably, thus bringing about national betrayals, revolutions, and secret negotiations with the enemy."

That's... intense.

And I mostly agree with him. Chasing pleasure as the main standard ruins character. I've seen it. The people who optimise for comfort, for weekends, for escape are often the same people who quietly admit their lives feel empty.

But Cicero feels almost too anti-pleasure. Life still needs joy. Rest. Recovery.

Here's my actual problem:

When I'm with friends now, I don't get the same joy I used to. I catch myself thinking: I'd rather be working on AION. I'd rather be reading. I'd rather be learning.

It's not that I've become some ascetic monk. I still go out. I still have fun. But the gap has widened.

Most of my friendships feel... shallow now. Not because they're bad people, but because the intellectual growth has diverged. The conversations I want—about systems, philosophy, building something that matters—aren't really there anymore.

And I don't know how to bridge that gap.

Part of me wonders if I'm the problem. Have I become boring? Too serious? Too obsessed with work?

Another part knows: my friends haven't "fallen behind". We've just grown in different directions.

They're optimising for comfort, stability, weekends.

I'm optimising for the seventy-year harvest.

Neither is "wrong". They're just increasingly incompatible.

So I'm in a strange place: I have friends, but I feel alone. I go out, but I'd rather be home. I enjoy myself, but I enjoy building more.

The twist Cicero would probably point out is this: what you find pleasurable reveals what you actually value.

A year ago, I got more pleasure from hanging out than from working. Now it's reversed.

That isn't virtue in itself. It's just a shift in what feels meaningful.

Building AION, reading philosophy, studying space economics—these aren't noble sacrifices I'm heroically making. They're genuinely more engaging, more satisfying, more pleasurable than anything else I could be doing.

The Stoics didn't see discipline as deprivation. They saw it as alignment—when what you want to do and what you should do become the same thing.

I'm not there yet. But I'm closer.

Where I'm still figuring it out:

I probably need more genuine rest. One full day off a week where I completely disconnect—not because I "should", but because systems need downtime. Even the best engines overheat if you never let them cool.

But I also don't want to force myself to "have fun" in ways that feel hollow. Going to the pub because "that's what you're supposed to do" is as empty as working 24/7 because "that's what hustlers do."

Cicero himself worried that extreme austerity can curdle into sourness—and I'm aware of that risk. I don't want to become the joyless grind who loses all sense of pleasure.

The version of temperance I'm aiming for isn't abstinence or hedonism. It's honesty about what actually brings me joy—even if that joy looks nothing like what most people expect.

Right now, that looks like: building things that matter, learning from people who lived 2,000 years ago, and accepting that the friendships I want don't exist yet—but might, once the foundations are built.

If Cicero's warning about "sensual greed" means anything, it's this: pleasures that don't compound are distractions. And the inverse: work that compounds isn't work. It's the highest form of pleasure.

I'm not a saint. I'm just someone whose definition of "fun" has shifted—and I'm still working out what that means.

The Laws I Want to Live By

Cicero gave me words for feelings I already had.

There is a higher law above any state, any company, any institution. A standard that exists whether or not it's written down, whether or not anyone enforces it.

Lives are judged at seventy, not twenty-seven. The qualities that matter—thought, character, judgement—compound over decades, not quarters.

Loneliness is the cost of high standards. That's fine. Better to be alone and honest than surrounded by people you don't respect.

What you find pleasurable reveals what you value. If your definition of "fun" shifts towards building, learning, and creating, that isn't sacrifice. It's alignment.

I don't know exactly what my business, my charity, or my seventy-year-old self will look like.

But Cicero helped me choose which laws I want to stand under.

Not the ones in the employee handbook. Not the ones that promise security in exchange for sleepwalking. Not the ones that say: get a degree, get a job, get a mortgage, retire, die.

The laws I'll still recognise as right when I'm old, tired, and looking back at the whole story:

Build things that compound. Business, knowledge, character, relationships that push you forward.

Live by higher law even when no one's watching. Especially when no one's watching.

Think in decades, not quarters. The seventy-year harvest matters more than the twenty-seven-year panic.

Accept loneliness as the price of integrity. The right people appear once the foundations are built.

Align pleasure with purpose. If the work is meaningful, it stops feeling like work.

At 27, I'm planting.

The harvest comes later.

And if Cicero—rejected, exiled, executed—can still shape how we think about law, duty, and character two thousand years after his death, then the timeline I'm on isn't too long.

It's exactly right.