Benjamin Franklin and the Proof That One Lifetime Is Enough

I've always been curious about Benjamin Franklin, but for most of my life, I only knew the caricature.

To me, he was the guy on the $100 bill. The kite and the key. Maybe that he signed the Declaration of Independence. That was the extent of it.

Recently, I've been systematically studying great thinkers as part of my own curriculum. Franklin was simply next on the list. But after watching the Ken Burns documentary and reading Walter Isaacson's biography, that caricature broke completely.

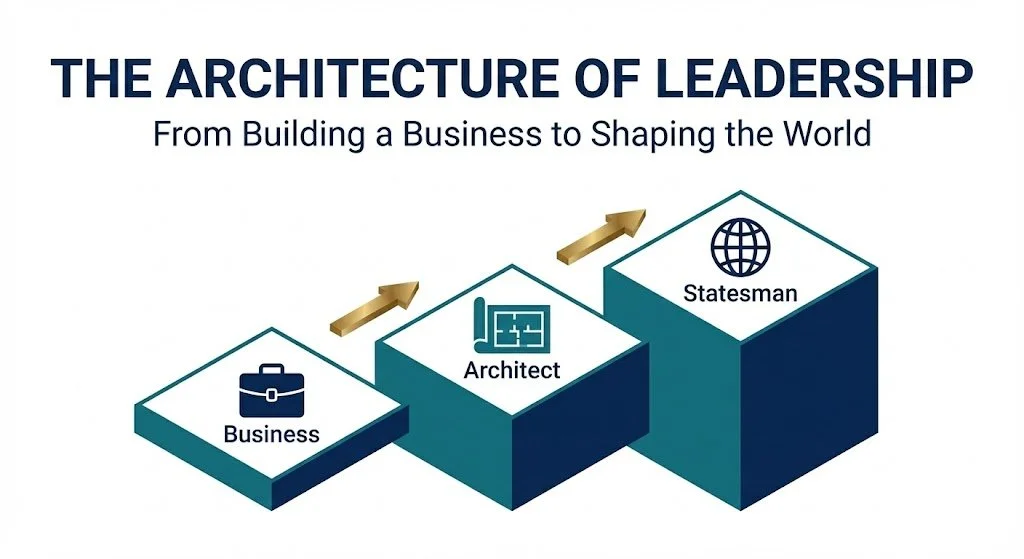

What emerged instead was a man who lived three full lives in one body:

The Printer — the grinder, the businessman, the builder of networks.

The Scientist — the researcher who retired early to question nature.

The Diplomat — the statesman who shaped nations without a crown.

No formal degree. No aristocratic title. Just a printing press and an obsession with reading.

And watching his life unfold, one question kept hitting me:

How did one man do this much in a single lifetime?

I’ve been watching these Ken Burns documentaries back-to-back lately — Jefferson, Washington, Da Vinci, now Franklin. Not for entertainment. For orientation. I’m 27, I’ve just walked away from a stable career, and I’m trying to rebuild my trajectory around something I actually respect.

Franklin matters to me because he makes the long game feel legitimate. Not “believe in yourself” legitimate — structurally legitimate.

A staged life. Business first. Then science. Then service at a higher level. And somehow it still adds up, centuries later.

Life 1: The Print Shop (The Grind)

The first thing about Franklin that hits me is how early he started working.

By age 10, he's earning. By his teens, he's in the printing world. He becomes a printer, then runs his own shop, then a newspaper. He writes, edits, sells, prints, delivers. There's no romance here. It's just grind.

But the print shop becomes his first laboratory.

He learns:

How information spreads

How people actually behave (not how they say they behave)

How to sell an idea, not just have one

From that foundation, he spins out the Junto (his leverage network), the first public library, a fire department, a hospital, and a college that eventually becomes the University of Pennsylvania.

The business phase isn't the end goal. It's the training ground. It teaches him how value, people, and systems work in the real world.

My Print Shop

I'm in my print shop phase right now. And honestly? It's terrifying.

I left what I call a "zombie job" at KPMG—reports no one read, work that didn't compound, just monthly paychecks and the slow realization I was sleepwalking—to build in the space economy.

On paper, this makes no sense. I have no engineering degree. I have no formal coding background. I'm entering one of the most technical industries on earth with a computer and an idea.

My print shop isn't about ink stains. It's about credibility.

Right now, that looks like: late nights in Cursor, shipping modules, breaking things, fixing them, learning fast. I'm building AION using AI-assisted development—not to pretend I'm a senior engineer, but to accelerate the build-test loop so I can ship something real.

I'm 90% through Module 2 of 4. It's December 2025. The employment cycle restarts in January. I'm racing to finish the MVP before that window closes.

AION isn't just a product. It's proof-of-work. It's the first thing I can point to and say: I didn't just read about the space economy—I built a tool for it.

Franklin didn't get to be a scientist until his printing business succeeded. I don't get to the research phase until this phase works.

That's Stage 1. Business phase. Apprentice phase. Proving I'm not just talk.

The Missing Junto

Franklin famously created the Junto—a club of mutual improvement where tradesmen and thinkers met to discuss ideas. It was his leverage network.

I look at my life right now, and I have to admit: I don't have a Junto yet.

I have friends. I have foundations. But a true Junto requires mutual professional respect, and right now, I'm still earning mine. When you quit a big firm to go solo, you lose your borrowed credibility. You're just a guy with an idea until you prove otherwise.

I've realized that the Junto doesn't come first. The work comes first. The people appear once you start making a name for yourself.

I'm building in silence right now so that eventually, I can build a table worth sitting at.

Life 2: The Architect (The Design Phase)

Franklin steps back from business around 42 and pivots into science.

Not because he's bored. Because he's built enough independence to follow curiosity without asking permission.

Electricity. Lightning rods. Bifocals. The Franklin stove. Ocean currents. Weather patterns.

His loop is simple:

Experiment → Observe → Publish → Iterate

He doesn't hoard the work. He doesn't try to monetize every insight. He shares. He compounds usefulness and reputation, not just money.

That's the move I'm paying attention to: not "become a scientist", but earn enough freedom to do deeper work.

My Version: The Architect

I don't think my Life 2 looks like Franklin's laboratory phase.

Once I've done well in the space industry—once I've built credibility, real expertise, and some independence—I want to shift from building individual products to designing the systems those products sit inside.

This is the Architect phase: work that's less about features and more about frameworks.

It looks like:

Deeper work on space economics, orbital risk, and governance (what actually makes orbital infrastructure investable and insurable)

Building institutions: research centres, study programmes, small think-tank style outputs that translate complexity into decisions

Designing capacity where it doesn't exist yet—especially for developing economies trying to enter the space race

Taking what I learn from space risk systems and applying the same thinking to other domains where incentives and uncertainty collide

Why "Architect" instead of "Scientist"?

Franklin's frontier was physics. Mine is systems design.

The space economy isn't just a technical problem—it's an institutional one. How do you price risk when there's no claims history? How do you convince capital markets to fund orbital infrastructure? How do you help a developing nation build space capability without importing broken incentives?

Those aren't engineering questions. They're architecture questions: designing the frameworks, governance structures, and economic models that make the technical work sustainable.

Franklin's "science" was electricity. Mine is systems design at scale.

Not just "here's a better underwriting engine", but:

"Here's how a country should think about space risk"

"Here's the institutional architecture that makes orbital infrastructure viable"

"Here's how you avoid importing the wrong incentives into a frontier industry"

This is also where philanthropy begins for me—but not as passive giving. More like building public infrastructure for thought: frameworks people can use, institutions that outlast a single product cycle.

That's where I'd like to be in my 40s.

But I can't skip the line. Franklin only got to play with lightning because he spent twenty years sweating over a printing press.

I only get to be an Architect if the Business phase works.

Life 3: The Statesman (The Duty)

Then there's the third life.

Franklin in London and Paris, surrounded by aristocrats and ministers. No crown. No army. But real influence.

He becomes a translator between worlds:

Colonies and empire

Enlightenment philosophy and rough political reality

Idealistic declarations and brutal incentives

He doesn't rule. But he shapes the rules.

My Version: The Statesman

This is the long game.

If Life 1 is building credibility in the space economy, and Life 2 is designing frameworks and institutions that actually work, then Life 3 is using that accumulated weight to help steer bigger systems.

Not as a consultant selling slide decks—but as someone who has built things, tested them, learned where reality pushes back, and can speak to both the technical layer and the institutional layer.

I'd like to contribute to Pakistan's space programme one day. And to other countries trying to build capability without repeating the same mistakes—not just technically, but economically and institutionally.

Concretely, that might look like:

Helping design national space policy frameworks

Advising on risk management and insurance structures for orbital assets

Building capacity programmes for space agencies in developing economies

Contributing to international governance discussions on orbital debris, liability, and coordination

This is the philosopher-king phase without the throne: not ruling, but helping shape the systems other people operate inside.

And Franklin's point—the point I keep coming back to—is that this can be staged:

Business → Architect → Statesman.

Each phase builds leverage for the next. That's the blueprint I'm aiming at.

Franklin's Virtues (And Where I'm Failing)

Underneath all of this, Franklin had a personal operating system: the 13 virtues he tracked in a notebook.

Temperance. Silence. Order. Resolution. Frugality. Industry. Sincerity. Justice. Moderation. Cleanliness. Tranquillity. Chastity. Humility.

What I like about it is that it isn't performative. He tracked them because he struggled with them. He wasn't writing from a pedestal—he was logging the work.

I feel that same friction every week.

Resolution: I tell myself I'll wake up at 7:00 and start the day properly. I wake up at 8:00.

Industry: I tell myself I'll read faster and deeper. I'm still averaging about a book a month.

Frugality: I tell myself I'll be more deliberate while I'm building. Then London happens—and the numbers move whether you like it or not.

It frustrates me because it doesn't feel like a small thing. When you've taken a risk, consistency becomes the whole game. Waking up late isn't "a lifestyle choice". It's time you don't get back.

But Franklin's real lesson is this: character is a design problem, not an identity.

You don't fail once and decide you're broken. You mark the X on the chart, then try to keep the column clean tomorrow.

For me, four of his principles feel like the core operating system:

Frugality — spend on things that compound

Truth/Sincerity — don't bullshit yourself

Industry — do the work for a long time

Kindness/Justice — don't trade decency for ambition

I'm 27. By Franklin's standards, I'm behind. He had already built momentum by this age.

I can't change the earlier chapters. I made choices that didn't compound the way I wish they had—a Law and History degree, a corporate job that taught me process but not systems thinking.

My friends and family think I'm crazy for leaving. And until I prove this risk paid off—until AION works, until Stage 1 is complete—they're right to think that.

But here's the difference: I'm awake now.

I know I'm behind. But I also know I have time to fix it.

The only thing that counts from here is what I build next.

Why This Matters to Me Right Now

It's easy to look at Franklin and think: different era, different rules, different world.

But he's proof of three things I genuinely need to believe right now:

1. Formal education is optional. Self-education isn't.

Franklin built himself out of books, work, and observation. I have access to more knowledge than he ever did—and now AI tools that make learning and building faster. The barrier isn't access. It's discipline.

2. You don't have to pick one identity for life.

Printer → scientist → diplomat. Three serious lives, one person. I don't need to be "just" one thing forever. I can stage it: build first, then design bigger systems, then serve at a higher level.

3. A life can be engineered in phases.

Each phase builds leverage for the next. That's the part that calms me down when I start spiralling about timelines.

Right now, I'm in the grind: building AION, finishing modules, tightening the work so it's real enough to stand behind when I speak to people in the industry.

I want it ready before the year turns—not because it's a deadline, but because I'm tired of having ambition without receipts.

Franklin's reminder is simple: this is Stage 1. It's not meant to feel like the end. It's meant to build the base.

If I do this phase properly, I unlock the next one.

Nothing is guaranteed—but the structure is sound.

The Blueprint

Franklin did all of this with a print shop and candlelight.

I have access to tools he couldn't imagine, and a frontier industry that still feels early enough to shape.

So the question I keep coming back to isn't "what would Franklin do?" It's simpler:

Am I doing the work that earns the next stage?

I'm in Life 1—the print shop phase—trying to make something real enough that it buys me the freedom to go deeper later.

The Architect phase and the Statesman phase can wait.

The only job right now is to make the press run.

Further Reading & Sources:

Ken Burns, Benjamin Franklin (PBS Documentary)

Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life